“The city is a big home for a big family” (Leon Battista Alberti)

29 June 2018

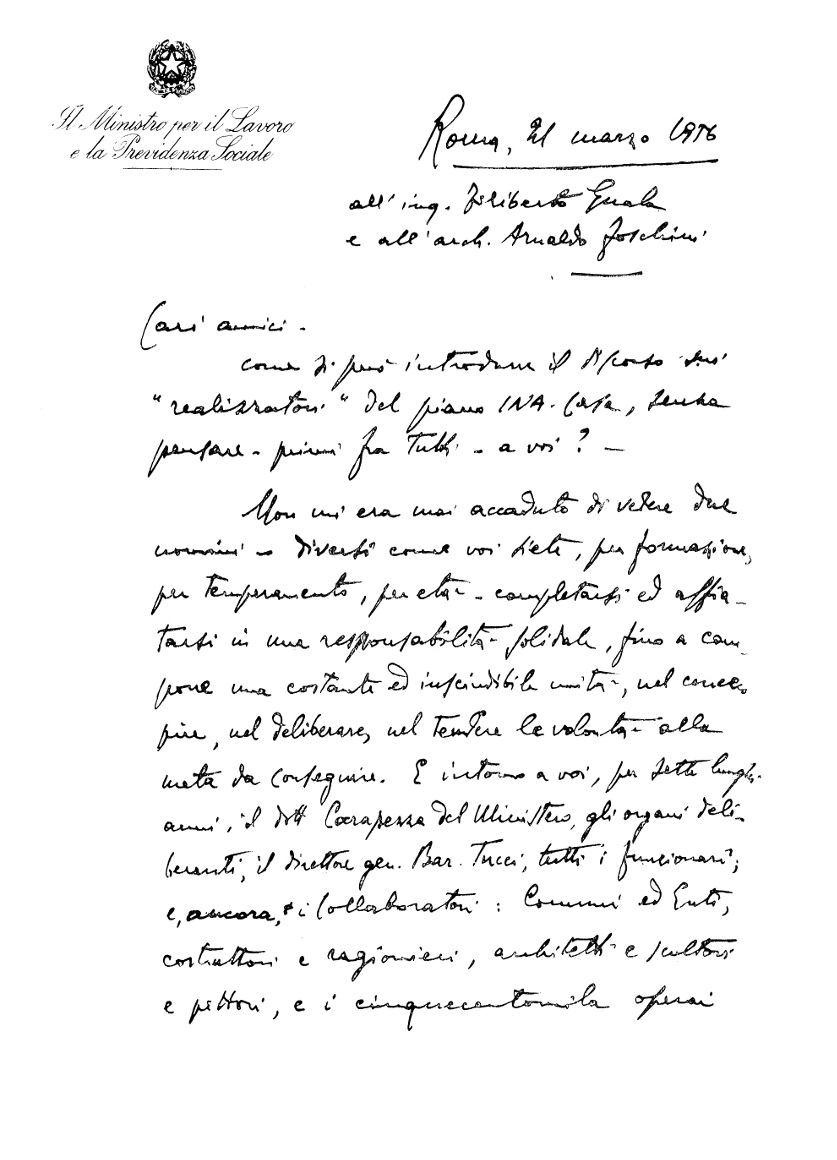

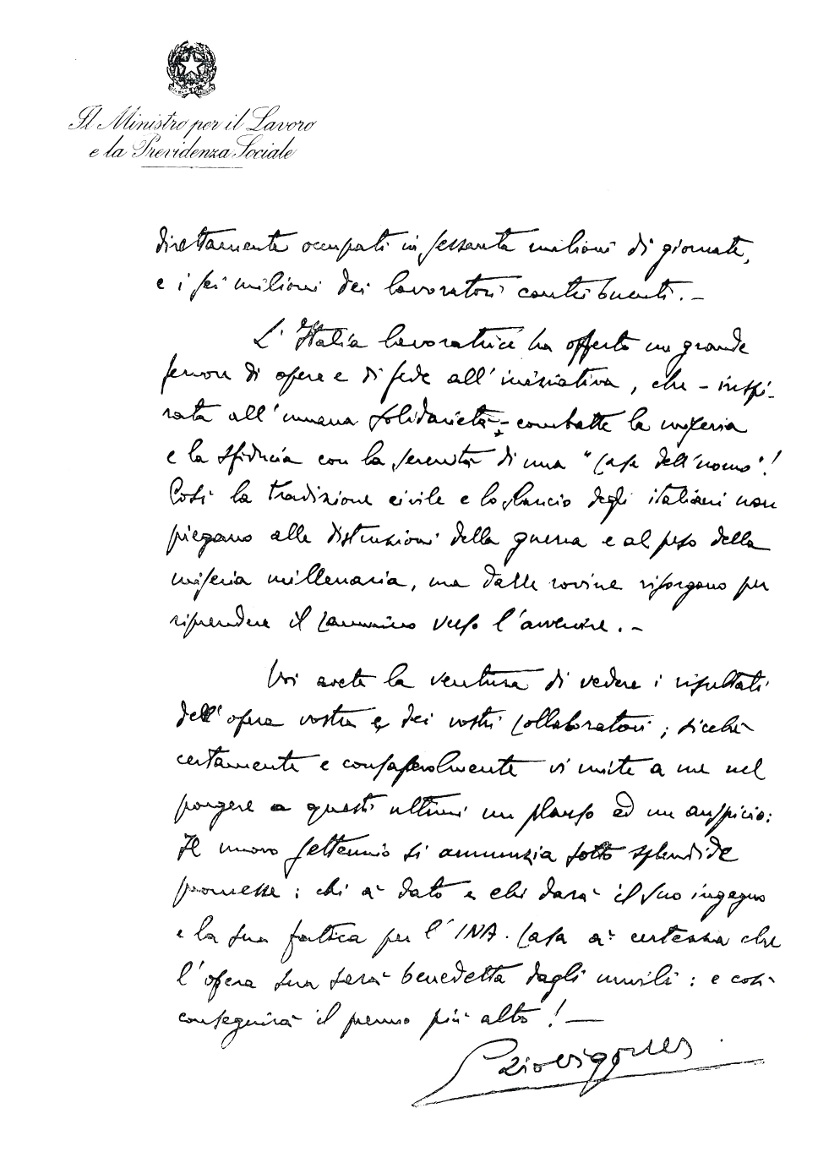

The neighbourhoods constructed under the INA-Casa Plan (1949-1963), during the post-war reconstruction years, remain an unrivalled example of residential popular housing on a national scale. The Plan, also known as the Fanfani Plan, after the politician and Minister of Labour and Social Policies (1947-1950), and later Prime Minister, who implemented it, passed into law on 28 February 1949, as Law No. 43, Provvedimenti per incrementare l’occupazione operaia, agevolando la costruzione di case per lavoratori [Plan to Increase Employment for Labourers: Facilitating the Construction of Homes for Workers].

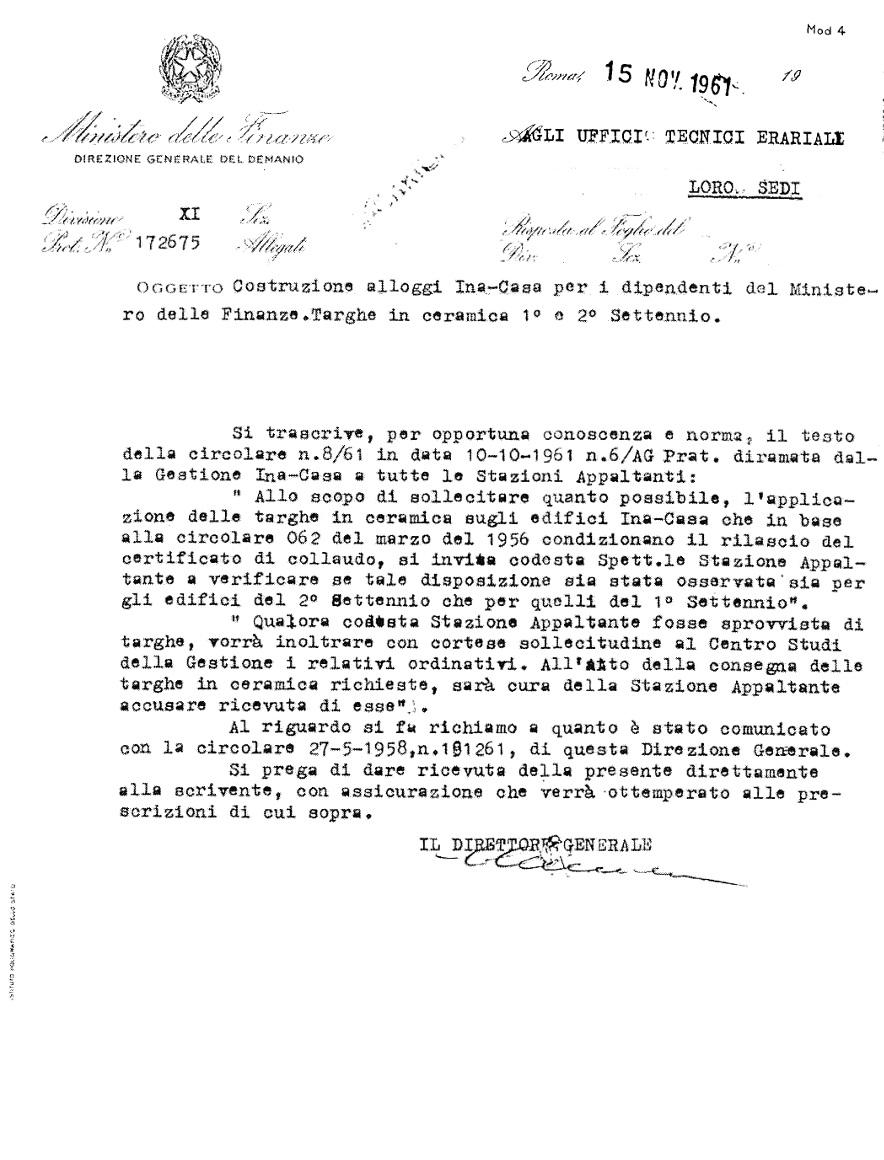

The technical consultancy committee behind the Plan, established by the INA, boasted renowned architects such as Adalberto Libera, Mario Ridolfi, Pier Luigi Nervi, Mario De Renzi, Saverio Muratori, as well as humanists such as the industrialist Adriano Olivetti, President of the Istituto nazionale di urbanistica [Italian National Institute of Planning] from 1950 to 1960. Those working on the interior included interior designers-architects such as Vittorio Gregotti, whilst the ceramic plaques with the INA-Casa signature, affixed to the buildings as an identifying feature of the Plan, were created by prominent artists and ceramists including Alberto Burri, Duilio Cambellotti, Piero Dorazio, Tommaso Cascella, Publio Morbiducci, Pietro De Laurentiis, Irene Kowaliska and Guerrino Tramonti.

On the whole, from the beginning to 1962, about 20,000 building sites were set up for the implementation of the Plan, where every year at least 40,000 workers could find a job; the Plan saw the participation of hundreds of public institutions and called for the contribution of thousands of private caompanies and independent professionals.

The INA-Assitalia Archive preserves traces of this great history, although several changes in ownership, from the GESCAL (Gestione case per lavoratori [Housing Management for Workers], liquidated in 1974) to the IACP (Istituti autonomi case popolari [Autonomous Institutes for Public Housing]) and finally to the ATER (Aziende territoriali di edilizia residenziale [Regional Companies for Residential Housing]), complicated the research process.

With the necessary documents, the Archive recently recovered the 1953 film reel Case per il popolo [Homes for the People], made under the auspieces of INA-Casa under the direction of Damiano Damiani and preserved by the Bologna Film Archive, which was responsible for digitising it. The film, which is about ten minutes long, features two off-screen voices, one male and one female, speaking over the images. The film begins with a description of the precarious health conditions of the people in the slums, with the images showing huts and caves (the man is described as “a modern day caveman”) and the emaciated faces of a group of street urchins who live in constant poverty. The protagonist, little Mariuccia, is forced to collect water with a jug several times a day from a single fountain which serves more than a hundred people. Then the images shift to the building sites and the INA housing plan in various phases of construction, and then to Mariuccia who finally gets a house with freshly-plastered walls and runs straight over to open a tap, joyously watching the water pouring out. The children look out from the balconies of the houses and play in the courtyards, before the final images show an aerial view of the INA-Casa neighbourhoods.

This neo-realist influenced documentary recalls Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Mamma Roma (1962), in which the protagonist, played by Anna Magnani, moves into a house in the Quadraro INA-Casa neighbourhood, the same one that appears in Damiani’s film. The Quadraro public district of Rome lies between the Via Tuscolana and the Via Tiburtina, and was noteworthy during the Second World War for its efforts in support of the Resistance and against the deportations, so much so that it was nicknamed “the hornet’s nest” by the Germans during the Nazi occupation.